Studying the Japanese language can be really frustrating at times, especially when you’re faced with complex kanji characters, tricky pronunciation, and nuanced grammar rules. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed and want to give up.

However, these challenges might be more manageable than they seem if you recognise and avoid these 10 common Japanese learning mistakes. By understanding these pitfalls, you can learn Japanese quicker and more efficiently. If you’re determined to master Japanese, then avoid making the following common Japanese learning mistakes!

One of the best ways to explore Tokyo is to visit the local areas and immerse yourself in the local culture. If you want to explore local areas, we have created scavenger hunt adventures personalised to your interests, filled with fun facts, clues and puzzles. If you’re curious, you can check out the games here! Check out the Flip Japan Games here! |

Top 10 Common Japanese Learning Mistakes

1. Stressing out over the Japanese writing language.

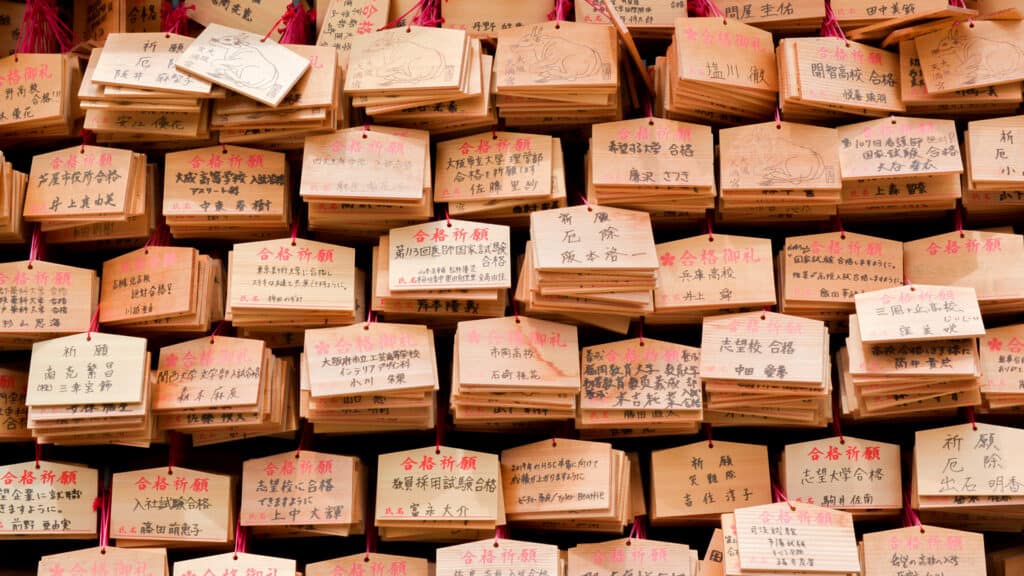

There are three written languages in Japanese: hiragana (ひらがな), katakana (カタカナ), and kanji (漢字). When studying Japanese, some people spend hours trying to perfect all three, and it’s usually for naught. Unless you’re taking an examination or planning to work in a corporate environment, you’ll almost never have to write.

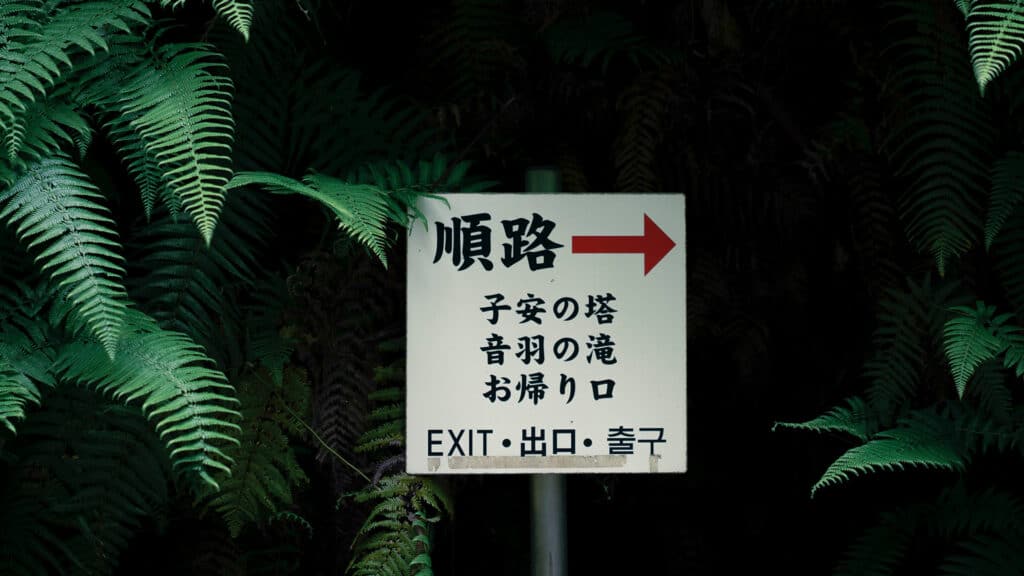

If you do want to master one or two of the written languages, then go with hiragana and katakana. They’re relatively easy to memorise, and they are used in some street signs, so they can be pretty useful.

The one you should avoid obsessing over is kanji, the dreaded Chinese characters. There are thousands of them, and they’re pronounced differently in different contexts, and trying to learn them all can make you feel really defeated. Learning a few every now and then can be pretty fun, but don’t spend too much time on it until later. For now, it’s too much effort for too little return.

2. Obsessing over Japanese grammar.

If you’ve already begun studying the Japanese language, then you’ll probably have torn a patch of hair out trying to understand the differences between ‘wa’ and ‘ga’, ‘de’ and ‘ni’, ‘sareru’ and ‘saseru’, and more.

You’ll be taught in classrooms and by textbooks that messing them up could have disastrous results but, like with the written languages, unless you’re taking an exam or applying for a job, messing up grammar isn’t the end of the world. Japanese people tend to be rather forgiving of common Japanese learning mistakes by foreigners, so there is no need to worry too much about it.

There’s one specific type of Japanese grammar that you absolutely should not obsess over: business Japanese. What conjugations you use in business Japanese depends on who you’re speaking with, their place in the hierarchy in relation to yours, whether you’re “lifting them up” or “putting yourself down”, what you’re asking of them, or what you’re telling them.

Business Japanese is so difficult to grasp that even Japanese people struggle with it, so much so that the top-selling books in March and April, when fresh graduates are about to enter the workforce, are textbooks on how to use business Japanese correctly. Just forget about business Japanese for now and focus on conversational Japanese grammar. It’s easier to grasp, more practical, and you’ll have more opportunities to practise it as well.

3. Saying “You”.

“You” in Japanese can be “anata (あなた)”, “kimi (きみ)” or “omae (おまえ)” (the latter two used primarily by men), but you’ll find that people rarely use those words in Japan. People will often omit the subject in the sentence as it’s understood by context.

For example, instead of asking your conversation partner, “where are you going (あなたはどこに行きますか, anata wa doko ni ikimasu ka)”, you would omit the subject in the sentence and simply ask “where going (どこに行きますか, doko ni ikimasu ka)”. It’s not wrong or offensive to address someone with “you”; you would just sound more natural if you speak like how Japanese people speak and omit the subject.

In the case you need to address a specific person (for example, if you’re in a group), you would refer to that person with their name. For example, instead of asking your friend Tanaka, “how are you” (あなたは元気ですか, anata wa genki desu ka), you’d say, “how is Tanaka” (田中は元気ですか, Tanaka wa genki desu ka).

4. Saying “I”.

Similar to ‘you’, there are three different ways of saying ‘I’: ‘watashi (わたし)’, ‘boku (ぼく)’ and ‘ore (おれ)’. ‘Watashi’ is rather soft and polite, used primarily by women or by people in the workplace when addressing a senior. ‘Boku’ and ‘ore’ are used primarily by men, the former being more humble and the latter being more aggressive or manly.

And just like with ‘you’, people often omit ‘I’. For example, if Tanaka wants to introduce himself, instead of saying “I am Tanaka (ぼくは田中です, boku wa Tanaka desu)”, he would introduce himself with just “am Tanaka” (田中です, Tanaka desu) as the subject ‘I’ is understood by context.

Some Japanese girls will refer to themselves in the third person, replacing ‘I’ with their own names as it’s “cuter”. For example, instead of saying “I want to eat (わたしはたべたいです, watashi wa tabetai desu)”, or omitting the ‘I’ (as we’ve discussed) and saying “want to eat (たべたいです, tabetai desu)”, a cute girl like Miki would say, “Miki wants to eat (ミキはたべたいです, Miki wa tabetai desu)”. Again, it’s not wrong to address yourself with ‘I’; you would just sound more natural if you didn’t.

5. Misusing suffixes.

Most people know of the suffix ‘-san (さん)’, which you attach to someone’s name to show respect and to be polite. For example, if you met Tanaka for the first time, you would refer to him as Tanaka-san (田中さん).

Some people make the Japanese mistake of attaching ‘-san’ to their own names, which you never do. If Tanaka wants to introduce himself, he would simply say “am Tanaka (田中です, Tanaka desu)” instead of “am Tanaka-san (田中さんです, Tanaka-san desu)”.

There are other suffixes such as ‘-chan (ちゃん)’, ‘-kun (くん)’, and ‘-sama (さま)’. ‘-chan’ is usually used when addressing someone or something cute, for example, a child or a puppy. Be sure not to use it with someone older than you or someone you’ve just met as it can come off as disrespectful or condescending. ‘-kun’ is used with men younger than you, usually if they’re still students instead of “shakai jins (社会人, working adults)”.

And lastly, ‘-sama’ is used with someone who’s of a higher status than you, and it’s used a lot by service staff to address customers. Like with ‘-san’, you don’t usually attach these suffixes to your own name.

6. Not being careful with short and long vowels.

When you’re studying the Japanese language, you will realise there are many words in Japanese that are pronounced very similarly and they are differentiated by short and long vowels. Here are some examples:

‘Obāsan (おばあさん)’ with a long ‘a’ means ‘grandmother’, and ‘obasan (おばさん)’ with a short ‘a’ means ‘aunt’.

‘Jūsho (じゅうしょ)’ with a long ‘u’ and short ‘o’ means ‘address’, and ‘jūshō (じゅうしょう)’ with a long ‘u’ and ‘o’ means ‘severe’.

Some Japanese words are derived from other languages, and long vowels will be indicated with a ‘ー’, as opposed to the examples above where long vowels are indicated by literally an additional vowel (‘oba-a-san’ vs ‘obasan’). Here are some examples:

‘Sūpā (スーパー)’ with a long ‘u’ and ‘a’ means ‘supermarket’, and ‘supa (スパ)’ with a short ‘u’ and ‘a’ means ‘spa’.

‘Bīru (ビール)’ with a long ‘i’ means ‘beer’, and ‘biru (ビル)’ with a short ‘i’ means ‘building’.

Some people may think that pronouncing the long vowels isn’t important, but as the examples above show, an innocent mispronunciation can lead to misunderstandings. So, be sure to draw out long vowels where necessary so you’re not directed to a spa the next time you ask where the supermarket is.

7. Not paying attention to syllables.

This common Japanese learning mistake that people make when studying the Japanese language is similar to the previous one, but instead of messing up short and long vowels, this mistake is about using the wrong vowel entirely, and this can lead to pretty awkward situations.

As you probably know, ‘kawaī (かわいい)’ means ‘cute’, but some people sometimes mispronounce it as ‘kowai (こわい)’ which means ‘scary’, and you definitely don’t want to accidentally offend a person by calling them scary when you’re actually trying to compliment them.

A friend of mine once wanted a pastry with bean paste filling, which is ‘anko (あんこ)’ but he accidentally asked for ‘unko (うんこ)’. It means ‘shit’. Literally. Thankfully, the lady behind the counter understood what he actually wanted and they just laughed it off, but this anecdote shows how crucial it is to get the proper vowels in a Japanese word.

8. Not minding your intonation.

Unlike the examples mentioned above, some Japanese words have the exact same spelling, short/long vowels and all, so to differentiate them in speaking, they have different intonations. For example, both ‘chopsticks’ and ‘bridge’ are spelled ‘hashi (はし)’, but ‘chopsticks’ is pronounced with a high ‘a’ and low ‘i’ (は↑し↓) and ‘bridge’ is pronounced the opposite way (は↓し↑).

Other examples include ‘candy’ and ‘rain’ which are both spelled ‘ame (あめ)’; ‘read’ and ‘call’ which are both spelled ‘yonde (よんで)’; and ‘kanji (the Chinese characters)’ and ‘feelings’ which are both spelled ‘kanji (かんじ)’.

When writing or reading, these words are differentiated by their kanji, but in speaking, they are differentiated by their intonation. Thankfully, there aren’t many words like these and most people will understand which word you’re referring to based on context. A restaurant server will understand that you want chopsticks, not a bridge, regardless of intonation.

9. Not using the Japanese ‘no’.

This one isn’t a mistake in the Japanese language but a misunderstanding of Japanese culture and customs. Rarely, if ever, do Japanese people say ‘no’, as Japanese society is very much non-confrontational. In place of ‘no’, they’ll say something vague such as “that’s a bit difficult (それはちょっと難しいですね, sore wa chotto muzukashii desu ne)” or they’ll just leave a sentence hanging, such as “Well… (えええ.., eee…; ちょっと…, chotto…)”, and wait for you to fill in the blanks and get the hint yourself.

If you’re in a restaurant and you’ve asked the waiter if you could replace your side salad with a side of fries, and they go, “that’s a bit difficult”, understand that that means ‘no’, and not that it’s doable but would take longer. If you’re inviting a Japanese friend out and they go “Well…”, they aren’t thinking it over; they mean ‘no’.

This is so deeply embedded in Japanese culture that it’s even taught in Japanese language classrooms (my Japanese language teacher literally made the entire class repeat and learn the phrase “Umm, well… (えええ…それはちょっと…, Eee… sore wa chotto…)” to say ‘no’. It’s evolved from a societal aspect into a linguistic one. It’s important to pick up on these Japanese social cues so you don’t land yourself in awkward situations that make everyone uncomfortable.

10. Misunderstanding “Ii desu”.

‘Ii (いい)’ is sometimes translated as ‘good’ or ‘okay’, but that’s not always the case. If you offer someone something, and they reply with “ii desu (いいです)”, they’re not actually saying “okay, I’ll take it.” Rather, they’re politely declining, saying, “No thank you”. It’s similar to English where we sometimes use “I’m good” or “I’m fine” to decline something. If you’re unsure which “ii desu (いいです)” a person means in a specific context, just ask to be sure!

Avoid These Common Japanese Learning Mistakes

There you have it, 10 of the most common Japanese learning mistakes people make when studying Japanese! These insights should help you avoid these common pitfalls and fast-track your success. Mastering Japanese can be a rewarding journey, but it does come with its challenges. According to a survey by the Japan Foundation, many learners find pronunciation and grammar to be the most challenging aspects.

However, by being aware of these common Japanese learning mistakes and taking steps to avoid them, you can make your learning process smoother and more enjoyable. Remember, practice and patience are key. For more tips and resources on how to study Japanese quickly and easily, click here.

Happy learning!